The Road to Emmaus and an Army of Artists

What do Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Turner, and Biblical Theology have to do with one another?

“Did not our hearts burn within us while he talked to us on the road, while he opened to us the Scriptures?” (Lk 24:32).

The post-resurrection scene in Luke 24 is a locus classicus for the belief that the OT Scriptures testify to the person and work of Jesus as the Christ. For the task of BT, this scene is rife with relevance.

Here the risen Christ engages his own disciples about the meaning of his incarnate life, death, and resurrection by referring to the message of the Hebrew Bible as a whole (Lk 24:27, 44). He later appears to them again, clarifies the gospel message that they are being called to proclaim among the nations by the power of the Spirit, and then ascends into the heavens (24:44–53).

Before this, though, Luke allows the scene to linger on Jesus’s initial encounter with the two disciples walking along the road to Emmaus. With intense theo-dramatic irony, Jesus prompts them to speak of “all that had happened in Jerusalem” these past few days. This hermeneutical trek through the OT ends as evening descends and they turn in for the night at Emmaus.

As they begin their evening meal, Jesus blessed the bread, broke it, and handed it to the disciples. At this moment, Luke recounts that “their eyes were opened, and they recognized him” (24:31). In that moment of recognition, Jesus disappears from their sight, and they are left to mull over his words and marvel at his recent presence in their midst.

In addition to biblical studies, this scene has a rich reception history in world of art. The supper at Emmaus is not the most frequently depicted biblical scene but it has captured the imagination of some of the most well-known artists across different periods of art history. Several artists also returned to this scene at different stages of their career.

For example, the Italian painter Caravaggio twice envisioned the moment of Christ’s revelation of himself to his disciples at the breaking of bread at the table. This is perhaps one of the most famous Emmaus paintings and it graces the covers of many works of biblical theology (Caravaggio’s Emmaus is to biblical theology what Rublev’s three visitors are to Trinitarian theology).

In his first painting (Supper at Emmaus, 1601), the colors are vibrant, the table meal is fresh and full, and the scene emphasizes the dramatic and discombobulating moment when Jesus’s identity dawns on the amazed disciples. Christ is at the center, blessing the bread with one hand and with the other reaches out almost toward the viewer. There is also an open seat at the table that is like a visual invitation to join the scene and consider the identity of Jesus as the resurrected Lord.

In his second painting (Supper at Emmaus, 1606), the tone is considerably darkened, the table and meal are much more sparse, and the features of Jesus and the disciples are more rugged and gritty (showing the details of age and almost conveying weariness). Whereas the first seems to emphasize the brilliant shock of the moment, the second draws the viewer into the Christological denouement with a sober and understated approach.

The Dutch Rembrandt also painted this scene multiple times in his lifetime. His first has a simple setting with Jesus’s figure on the right side of the canvas being illuminated from behind by candlelight (Supper at Emmaus, 1629). One disciple is in the light and leaning away from Christ in shock, and the other is fully in the shadow bowing at Jesus’s feet after falling out of his chair.

About twenty years later, Rembrandt returned to this scene in a more well-known work (The Supper at Emmaus, 1648, which now hangs at The Louvre). In this version, the perspective has shifted, and Jesus is now at the center of the table. The room is brighter from window light and a halo-like radiance flows from behind Jesus’s head as he begins to break the bread. The table in front of Jesus has also been cleared and the bright white tablecloth is reminiscent of the ceremonial setting of the Eucharist.

In their repeated treatment of this scene, both of these painters utilize techniques of shadow, light, tone, and color to convey a range of interpretive emphases. Caravaggio shifted from vibrant features to understated elements. Rembrandt moved from a simple atmosphere to an almost sanctuary-like setting.

With these two kinds of depictions, perhaps these artists wanted to explore both the joy and cost of discipleship. Sometimes lavish, sometimes sparse. Feast and famine. The freshness of insight alongside the fatigue of endurance. The revelation of Christ and the realization of the cross. In this sometimes confusing human condition, Christ still beckons you to join him at the table. Taste and see.

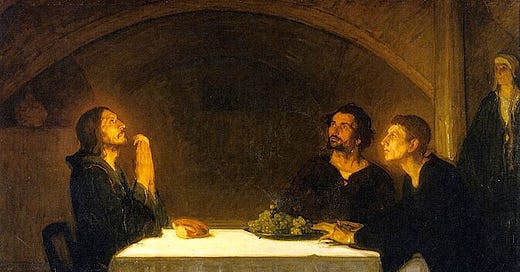

One of my favorite paintings of this scene is less well-known but nevertheless a significant entry in the reception history of this theologically rich table scene. In the middle of his career, American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) envisioned this scene with similarities and key differences to the works by other artists (The Pilgrims at Emmaus, 1905).

Tanner’s mother was a former slave, and his father was a minister and abolitionist. Tanner himself overcame racism that hindered his education as a student and went on to become the first African American artist to gain international acclaim (especially in France).

Perhaps from the influence of his father, as he approached middle-age, Tanner rededicated himself to the Christian life and began to focus his art on biblical scenes (some of his most well-known paintings are The Resurrection of Lazarus, 1898 and the Annunciation, 1898).

In his Emmaus painting, Tanner calls the disciples “pilgrims” and gives the scene a quiet and warm atmosphere. The table is bright white with the bread and a plate of fruit clearly visible. Tanner is known for his experiments with the depiction of light, and here the room is dim with dark shadows beneath the table and around the room. Because Jesus and the two disciples are dressed in dark clothes, the white tablecloth on Jesus’s side of the table is particularly bright.

A warm light is emanating from Jesus’s face and hands as the scene captures the moment of blessing the bread. Jesus’s face is radiant with an uplifted gaze, but you can still see the lines on his face and the scruff of his facial hair. The warm light from Jesus is reflected in the faces of the two disciples who look as if they are in the seconds directly before identity of the risen Christ dawns on them.

As Caravaggio and Rembrandt had done before him, Tanner memorably illustrates Luke’s narrative portrayal of a scene that marks the beginning of a new covenant era of the life of faith and ecclesial fellowship. These artistic attempts to capture the brilliance of Christ’s revelation and the shock of its reception among his disciples put the vibrant dynamic of Christian discipleship on full display.

In their central task, biblical theologians are like artists who read and reflect on the meaning of individual passages and the message of the biblical canon as a whole. They then attempt to portray the unchanging truth of this unbreakable word in creative ways that help us see the literary beauty, the theological depth, and the shimmering brilliance of these sacred texts.

This is why the task of biblical theology will last until the end of days and require a great cloud of witnesses. We need sketch artists, casual painters, masters of technique and style, amateurs making stick figures, and children drawing in the sand. We need sidewalk chalk, booths at the bazaar, satellite imagery, drone footage, exhibits in the museum, and formal portraits in the national gallery. However talented and competent a work of art might be, the grand storyline God’s work in the world will never be captured by a lone virtuoso.

It requires an army of artists. So join up. Get to work with whatever tools you have.

Keep painting your little piece in the mosaic of the story God is calling into being.