1. What is a Canonical Approach?

Primer on the Canonical Approach

What is a Canonical Approach?

A canonical approach to biblical studies suggests that the final form of individual biblical texts and the literary associations found within biblical sub-collections are a meaningful part of the interpretive task.

This focus on a given text’s compositional shape and canonical location does not exhaust a reader’s entire hermeneutical framework, but it does inform many of the decisions and commitments involved in biblical interpretation. Most proponents of a canonical approach connect their understanding of these concepts in some way to an account of the process of canon formation. This way of reading, then, is something that would have been possible from the earliest circulation of biblical texts and canonical collections.

What do the notions of “compositional shape” and “canonical location” mean?

Compositional Shape: Reading Biblical Texts in Light of Book-level Meaning

Compositional shape refers to the structure of a text taken as a coherent literary entity. Here the focus is on the strategy an author has used in order to communicate meaning in a written text. Meaningful inner-textual features that are involved in an author’s compositional strategy include choice of genre, the internal logic of opening and closing sections, and the interplay of thematic trajectories that are developed within the scope of a work. Attention to these types of literary features indicate that an interpreter is reading a text in light of book-level meaning.

For example, someone interpreting the historical record of the prophet Jonah or reading Jonah 1–3 might conclude that the prophet Jonah initially fled from Nineveh because he was afraid the people would not listen to him and perish. However, the shape of the prophetic book of Jonah 1–4 clarifies the prophet’s motives and rules out this initial reading. Someone interpreting the story in light of the book-level meaning generated by the Jonah narrative would note that the prophet initially flees Nineveh because he was afraid the people would listen and be delivered (Jonah 4:1–3).

Canonical Location: Reading Biblical Books as Part of Canonical Collections

Canonical location refers to the literary context of a biblical book within a particular collection. The focus here is on the possible meaningful effect that might result from inclusion within a grouping of other texts or a particular arrangement in relation to a sequence of other texts. A biblical book’s presence in a distinct sub-collection of related works, for example, would encourage an association of some kind between these texts.

For example, the presence of Leviticus within the established literary context of the “book of Moses” connects it invariably to both the theme of creation (in relation to Genesis) as well as the history of Israel after their time in Egypt (in relation to Exodus and Numbers). The “canonical context,” then, would be the broader literary setting that has been formed by the grouping of a series of sub-collections. So, for example, the books in the prophetic history (Joshua through Kings) would be associated with the narrative and theological themes brokered in the Pentateuch.

Ecclesial Function: Reading the Bible within a Textual Community

Ecclesial function refers to the social context in which biblical texts were initially composed, received, and collected for future generations of readers. The presence of a received canon in the history of the church shows that a community existed that consciously preserved and gathered together the writings they viewed as authoritative Scripture. In other words, the churches not only received and treasured the biblical writings, they also handed them down to later generations in a way that would maintain their compositional shape and extend their literary legacy.

In fact, the concept of canon implies that these authoritative writings were collected for the purpose of preserving them for future generations of readers. A community guided by the message of the prophets and apostles gathered their respective writings into collections and groupings. Members from this community then passed along these Scriptures in these groupings within an authoritative canon. Because of their location within this canonical collection, each of the individual biblical writings could more easily reach a broader readership. Though communities of believers can no longer be guided by the actual hands of the prophets and apostles, they can be guided by their handiwork.

A broad observation that we can make at this point is that these Jewish and Christian believing communities have always been textual communities. From the beginning, these communities were founded upon and centered around a collection of texts. These textual communities, in turn, gathered together and passed along the sacred writings for future generations of readers. Along with the compositional shape and canonical location of biblical texts, this attention to the ecclesial function of the biblical canon rounds out some of the focal points of a canonical approach.

Clarifying the Object of Study: Reading a Canonical Text

“The first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship from a corkscrew to a cathedral is to know what it is—what it was intended to do and how it is meant to be used. . . . The first thing is to understand the object before you: as long as you think the corkscrew was meant for opening tins or the cathedral for entertaining tourists you can say nothing to the purpose about them.”

—C. S. Lewis, “Preface to Paradise Lost”

The rationale for a “canonical approach” is directly related to the Bible as the proper object of study. In other words, a canonical approach is appropriate when reading a canonical text (i.e., a coherent literary work that is viewed both as authoritative and in relation to a broader collection).

How we define the biblical canon, then, is not only a helpful part of introductory matters but also a foundational element that structures one’s entire course of study in this area.

We Need an Appropriately Complex Construal of Canon (theological, literary, historical)

With these clarifications in mind, we can consider the dimensions involved when asking the question, “What is the Bible?”

In order to give the fullest account of the Christian canon, we have to recognize the varied types of study that are required. In particular, we ask this question: Is the biblical canon best understood in historical, theological, or literary terms? In our study, we want to always keep in mind that these three lines of analysis are not at odds. In fact, they are each necessary to understand the biblical canon most fully. To illustrate, we can use this working definition: The biblical canon is God’s word to his people.

Just like a piece of luggage, this theological formulation needs to be unpacked in order for it to help us. This definition of the biblical canon can be unpacked in three major ways. We can see these aspects by emphasizing different parts of the definition.

The Theological Aspect: The Bible is God’s Word to his people. The theological emphasis highlights the way God uses the Scriptures in his plan of redemption. The Scriptures are the means by which God reveals and calls people to himself. An evangelical approach to reading the Bible as Scripture is built around the profoundly theological claim that God speaks through written texts.

The Literary Aspect: The Bible is God’s Word to his people. This aspect highlights the verbal aspects of the canon as a collection of literary writings (i.e. words!) that require skillful reading and interpretation. Because the Scriptures come in different literary forms (genres), readers must be able to account for a collection that includes genres as diverse as narrative, poetry, epistle, and apocalypse.

The Historical Aspect: The Bible is God’s word to his people. This aspect highlights the historical location of the canon and its gradual development among a believing community of authors and readers. Recognizing the way biblical literature functioned within the believing community can shed significant light on the story of canon formation.

In order to grapple with the nature of the biblical canon as a coherent collection of scriptural texts, we must account for each of these areas. If we exclude one of these aspects or if we choose to emphasize only one of them, we will not do justice to all that the Bible is.

For example, if we only stressed the theological aspect, we might neglect the many literary tools needed to read the different types of biblical texts (e.g., a “rock” in a narrative account means something very different than a “rock” in a poem). If we only stressed the historical aspect, we would not be able to account for the way God speaks in these texts and transforms the lives of believing readers.

The fullest definition of the scriptural canon will incorporate all three elements, including authors, texts, and readers.

In light of these definitional starting points, a “canonical approach” would be one that seeks to make use of each of these dimensions. Historically, the Bible formed as authors wrote and believing communities gathered these texts together. Theologically, these individual texts and this collection as a whole has been guided by God’s special revelation and providential guidance. Hermeneutically, the shape of biblical books and their canonical context within a collection affect how they are received and understood by readers.

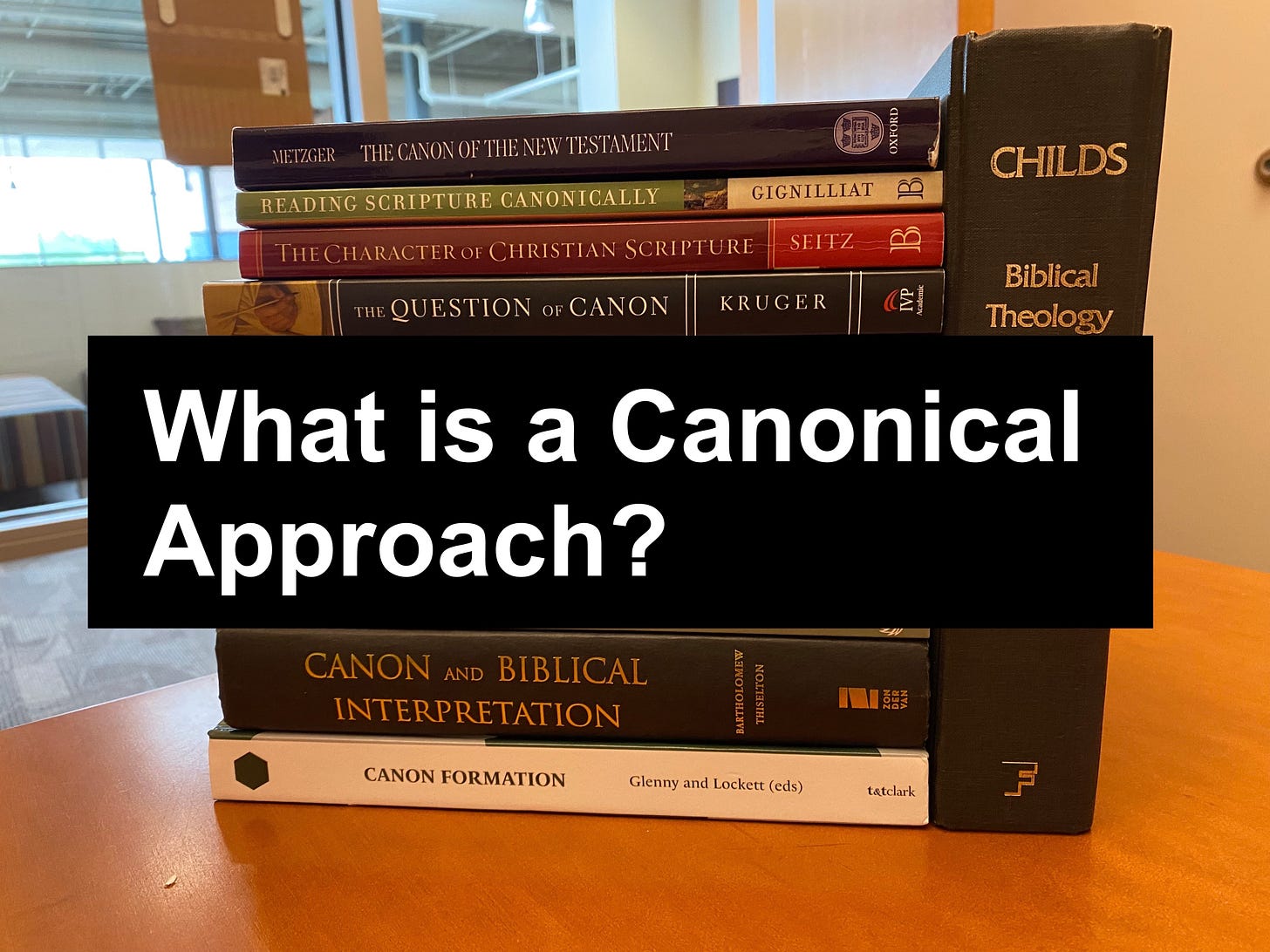

Annotated Walking Tour

There are many places to begin further reading and research on the biblical canon and a canonical approach, but working through this scholarship will catch you up to speed on some of the historical, textual, and theological issues that are central to the scholarly discussion about the biblical canon (for a list of works on canon formation, or “how the Bible came to be,” see here). Toward the end of this series, there will also be a series of posts showcasing the corpus of several of these writers.

The Canon Debate, edited by Lee M. McDonald and James Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002). This substantial volume includes 32 essays on the full range of issues and debates in the field of canon studies. While the contributors capture the general consensus in biblical studies on the canon question at the turn of the century, this material is for the most part still very useful because it demonstrates the scale of the study of the biblical canon (the range of historical questions it raises and the necessarily interdisciplinary nature of the task). Most of the contributors also represent the position in the biblical studies guild that views canon as a late feature of reception history in early Christianity (a 3rd/4th century phenomenon), that sees a strong distinction between “canon” and “scripture,” and that prioritizes the use of non-canonical literature in a comparative history-of-religions study of biblical literature. This volume will therefore also give you a snapshot of the scholarly positions that a “canonical approach” is in dialogue and often in tension with.

Canon Formation: Tracing the Role of Sub-Collections in the Biblical Canon, edited by W. E. Glenny and Darian Lockett (2023). This group of 16 essays examines each of the significant sub-collections in the biblical canon. Included also are several entries that reflect on the issues involved in studying the Bible on this larger scale. Each of the contributors has a shared belief in the strategic significance of the biblical canon and the importance of canonical sub-collections while also navigating issues of method and approach in different ways. This volume can also be fruitful paired with the Canon Debate volume. On the whole, they both fully engage some of the central issues in the discussion but also represent some of the key differences between different camps. Perhaps most directly, the Canon Formation volume typically argues for the meaningful relevance of the canon for biblical interpretation (rather than only a feature of reception history, etc). McDonald’s foreword serves as a nice touchpoint to the prevailing perspective of the Canon Debate volume (as the list of historical questions he raises illuminates some of the contrasting starting points).

Canon and Biblical Interpretation, edited by Craig Bartholomew, et al (Zondervan, 2006). This is the seventh volume in the Scripture and Hermeneutics Series and explores the relationship between the canonical approach and the theological interpretation of Scripture. Several serious essays on method and also on the practice of “canonical interpretation” across the biblical collection. This volume complements the two collections of essays above by moving toward the task of exegesis and biblical theology more directly. The essays by Thiselton, Childs, Seitz, Chapman, and Dempster are particularly helpful starting points.

Brevard Childs, Biblical Theology of the Old and New Testaments (Fortress, 1994), pp. 55–94. In this section of Childs’s magnum opus (“A Search for a New Approach”), he discusses the nature of the Christian Bible as a Two-Testament witness, delineates his understanding of canon and the nature of canon formation, connects this final form to the theological “witness” of Scripture’s “subject matter,” and outlines the canonical categories that he will use to structure his account of biblical theology. This brief section is the clearest articulation from Childs himself of what he means by a canonical approach.

Christopher Seitz, Character of Christian Scripture: The Significance of a Two-Testament Bible (Baker, 2011). This book is an excellent entryway into Seitz’s larger corpus. He begins with a lengthy discussion of the canonical approach and responds to common criticisms from the field of biblical studies. Throughout, Seitz argues for the abiding significance of the OT as Christian Scripture on its own terms (and not only what the NT makes of it). He also includes several exegetical examples and forays into the history of interpretation (e.g., the canonical function of Hebrews & the rule of faith). This volume would be good training grounds for working through Seitz’s more comprehensive The Elder Testament: Canon, Theology, Trinity (Baylor, 2018).

Mark S. Gignilliat, Reading the Bible Canonically: Theological Instincts for Old Testament Interpretation (Baker, 2019). A succinct orientation to the core issues involved in a canonical approach to reading the Bible. Gignilliat sees the canonical approach as a set of “theological instincts” that a reader brings to bear on the interpretive task. This slender volume is the best contemporary introduction to the canonical approach that traces its lineage through Seitz and Childs.

Stephen B. Chapman, “The Canon Debate: What it is and Why it Matters” Journal of Theological Interpretation 4.2 (2010): 273–94. Chapman’s article is a perfect primer to the issues that underlie the “canon debate” in the scholarly guilds. This would be a good article to read prior to surveying the collection of essays mentioned above.

Michael J. Kruger, “The Definition of the Term Canon: Exclusive or Multi-Dimensional?” Tyndale Bulletin 63.1 (2012): 1–20. Kruger examines the etymology, ancient function, and contemporary usage of the term “canon” and provides a helpful rundown of the historical, hermeneutical, and theological implications of one’s definitional decision. This article serves as a nice on-ramp to Kruger’s other works in this area (e.g., Canon Revisited and The Question of Canon).

Spellman, Toward a Canon-Conscious Reading of the Bible, chapters 1–2. In these first two chapters, I work through the canon formation discussion in light of the types of works mentioned here. Specifically, I examine the “broad” and “narrow” definitions of canon and consider the strategic significance of the notion of “canon-consciousness” for understanding the process of composition and canonization.

Obviously, there are many other works that might be added to this list, but these would provide a broad foundation to begin reading, studying, and researching in the field of canon studies. This post also aims to serve as an orientation to the definitions and scholarly angles that I’ll be exploring for the rest of the series.

In the next grouping of posts, we will briefly examine each of the major canonical sub-collections and reflect on some of the benefits of a “canonical reading” of these groupings of biblical books.

I wrote my M.Div thesis on Childs and canonical interpretation for the church, and it has been so helpful in trying to teach the "big picture" of scripture, even (especially?) to teenagers, who are often stuck in verse-of-the-day, personal application kind of stuff.